We all knew interest rates would eventually go up, but that doesn't mean the move this year has been pleasant. Since May 1, when the yield on 10-year Treasury bonds hit its low for the year (1.61%), long-term rates have risen by more than a full percentage point. This riled the bond market, where investors have suffered losses from their bond holdings. The impact on the stock market--in general--has been less troublesome: Volatility increased for a while, but the S&P 500 has gone on to reach all-time highs.

Still, the universe of high-quality, high-payout stocks often reacts more strongly to trends in the bond market than the S&P. If you consume a fair amount of financial media, you've probably heard--repeatedly and vigorously--that the "dividend trade" is over. For hedge funds and speculators, that may indeed be true. History suggests that rises in the yield of 10-year Treasury bonds are indeed correlated with market-lagging returns on high-dividend stocks, though not necessarily losses in absolute terms. I don't find this fact all that interesting, let alone worthy of action, but it's always worth being prepared for a bumpier road.

But is the threat of higher interest rates sufficient to warrant a change in the basic strategy of Dividend Investor, or perhaps a wholesale departure for greener pastures? I don't think so. Every approach entails some risk; given the other merits of our strategy--including an insistence on economic moats and rewarding dividend growth--interest-rate risk is one I’m willing to take.

What Does History Say?

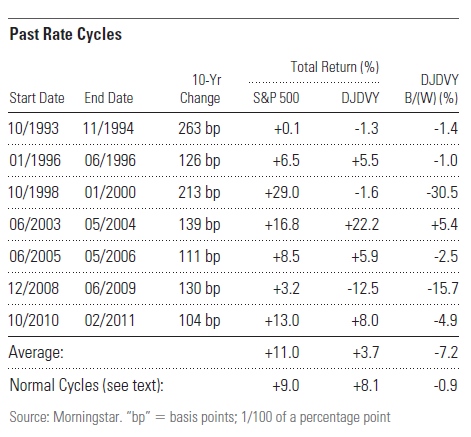

To get a sense of what we might expect in a cycle of rising long-term interest rates, I sliced and diced a bunch of historical data. I defined a rising-rate cycle as any move of 1 percentage point or more from a recent low, using monthly average values for the 10-year Treasury yield. Prior to the current cycle, there have been seven such periods since 1992. On average, these moves lasted 9.3 months and saw the yield on 10-year Treasury bonds increase by 1.55 percentage points.

It appears that the market in general has little to fear from these moves, as the average total return of the S&P 500 during these rising-rate environments has been 11.0%. For reference, the annualized total return of the S&P 500 since year-end 1991 comes in at 8.9%. Furthermore, the S&P recorded a positive total return in all seven periods of rising rates.

For high-yielding stocks, the verdict of history is somewhat less appealing--at least for investors who expect, or need, to outperform the market during short time horizons. The Dow Jones U.S. Select Dividend Index (hereinafter referred to as DJDVY) has trounced the S&P 500 since the end of 1991 with a compound annual total return of 12%. Better yet, its monthly beta has been only 0.78--that is, its monthly returns have experienced 78% of the volatility of the S&P. That said, in the rising-rate cycles described above, DJDVY has trailed the S&P with total returns averaging 3.7%. In three of the seven periods, DJDVY lost value, even with its ample dividends included.

However, these averages are skewed by two truly bizarre periods. The defining feature of the 1998-2000 stretch was not the rise in long-term interest rates, but rather the apex of the 1990s tech bubble. With the market seized by a speculative frenzy, otherwise sound common stocks were dumped for no sin greater than lacking ".com" in their names. Subsequent performance bears this out: In the two years following the March 2000 peak in the S&P, DJDVY earned a 61.5% positive total return while the S&P lost 21.5%. The other aberrant period runs from December 2008 through June 2009, when investors were gripped by panic: The yield on 10-year Treasury bonds plunged more than a full percentage point in December 2008, followed by a rapid bounceback. Excluding these two periods in hopes of identifying more natural relations between interest rates and stocks, DJDVY tends to lag the S&P only slightly.

However, these averages are skewed by two truly bizarre periods. The defining feature of the 1998-2000 stretch was not the rise in long-term interest rates, but rather the apex of the 1990s tech bubble. With the market seized by a speculative frenzy, otherwise sound common stocks were dumped for no sin greater than lacking ".com" in their names. Subsequent performance bears this out: In the two years following the March 2000 peak in the S&P, DJDVY earned a 61.5% positive total return while the S&P lost 21.5%. The other aberrant period runs from December 2008 through June 2009, when investors were gripped by panic: The yield on 10-year Treasury bonds plunged more than a full percentage point in December 2008, followed by a rapid bounceback. Excluding these two periods in hopes of identifying more natural relations between interest rates and stocks, DJDVY tends to lag the S&P only slightly.

Of course, no two interest-rate cycles are alike, and it may be misleading to read too much into data like this. However, the moves most analogous to our current one are probably 1993-94 and 2003-04. In both cases, short-term rates had previously been pegged at unusually low levels following financial stresses, the pace of economic recovery was disappointingly slow, and long-term rates started to rise before the Federal Reserve actually tightened policy. DJDVY underperformed modestly in the first period and actually beat the S&P 500 in the second.

In part 2, we will look at the relationship between interest rates and intrinsic value, and answer the key question: What’s priced in?