In part 1 of this article, we looked at how equal-weighting the S&P500 has performed, let’s explore further.

Case Closed?

Not so fast. While equal weighting addresses concerns related to single stocks, sectors, and so on, its predominant effect on the composure of the index’s portfolio relative to its cap-weighted parent is to give greater weightings to smaller stocks. According to S&P Dow Jones Indices, the top 10 constituents of the S&P 500 accounted for 18.1% of the index’s value as of Sept. 30, while the top 10 stocks in the equal-weighted version accounted for just 2.2% of the index’s value. Over the long term, this skew toward smaller-cap names has yielded greater returns relative to the cap-weighted S&P 500 at the cost of relatively greater volatility. In other words, from a diversification, risk, and return perspective, the equal-weighted S&P 500 looks an awful lot like a mid-cap portfolio.

Pay No Attention to the Mid-Cap Fund Behind the Curtain

At first blush, the equal-weighted S&P 500 bears a striking resemblance to a mid-cap fund, but what do the numbers tell us? The EW/400 line in last week’s Exhibit 1 plots the relative wealth generated by an investment in the equal-weighted S&P 500 versus the S&P MidCap 400 Index. The result is starkly different from the relationship between the equal-weighted S&P 500 and its cap-weighted parent. For much of the past 15-plus years, the equal-weighted S&P 500 and the cap-weighted mid-cap indexes have been in a dead heat, as evidenced by the flatness of the EW/400 line over that span. That said, the mid-cap index has outperformed the equal-weighted S&P 500 during the past 25 years.

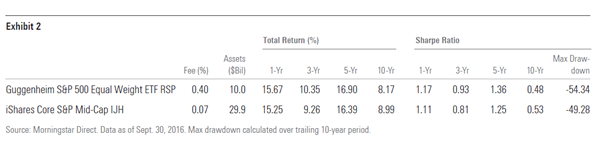

In Exhibit 2, I’ve included some figures measuring the performance of a pair of ETFs that track each benchmark: RSP, which follows the S&P 500 Equal Weighted Index, and iShares Core S&P Mid-Cap (IJH), which tracks the S&P MidCap 400 Index. On both an absolute and risk-adjusted basis, the funds produced remarkably similar results during the 10-year period ended Sept. 30, 2016.

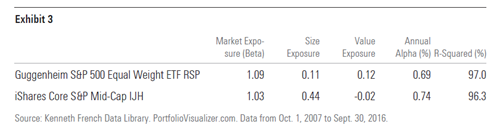

The data in Exhibit 3 provide a better sense of what’s driving the similarities between the two funds’ performance. Using the Fama-French factor regression analysis tool on Portfoliovisualizer.com (one of my favorite free online tools), I’ve run a standard Fama- French three-factor regression to distill each fund’s trailing 10-year returns into its constituent factors. Given the fact that both funds skew further down the market-cap spectrum, the results are what you might expect. Both funds have betas above 1 and statistically significant size exposure (they’re picking up the small-cap premium).

If RSP and IJH are effectively indistinguishable from one another on the basis of their risk/return profiles and factor loadings, then why would an investor choose one over the other? It is awfully difficult for me to see the case for investing in an equal-weighted fund like RSP for two key reasons. The first is straightforward: RSP is much more expensive. Paying a fee of 0.40% for a fund that will likely continue to yield results substantially similar to one that charges 0.07% is difficult to justify. Interim bouts of under- or outperformance of one fund relative to the other are inevitable over the long term, but fees are forever. The second reason is more context-specific. Depending on the makeup of an investor’s portfolio, investing in an equal-weighted fund like RSP might actually detract from the overall level of diversification at the portfolio level. Specifically, if an investor already has an allocation to U.S. large-cap stocks, adding RSP to the mix will likely just layer on additional exposure to many of the same names. The constituents of the S&P Mid- Cap 400 Index are, by design, completely distinct from those of its large-cap sibling. Thus, an investment in a dedicated mid-cap fund reduces the likelihood of overlap with existing large-cap allocations and stands to improve overall portfolio diversification.

Key Take-Aways:

• Equal weighting can mitigate the single-security-, sector-, and country-level concentrations that have historically been the Achilles’ heel of cap-weighted indexes.

• The predominant effect of equally weighting an index portfolio is to tilt it toward smaller stocks.

• In the case of a selection universe of large-cap stocks like the S&P 500, the equal-weighted portfolio will likely bear a striking resemblance to its mid-cap sibling.

• It’s difficult to make a case for equal-weighted funds as they tend to be more expensive than cap-weighted peers offering similar exposures and could potentially detract from diversification at the portfolio level.