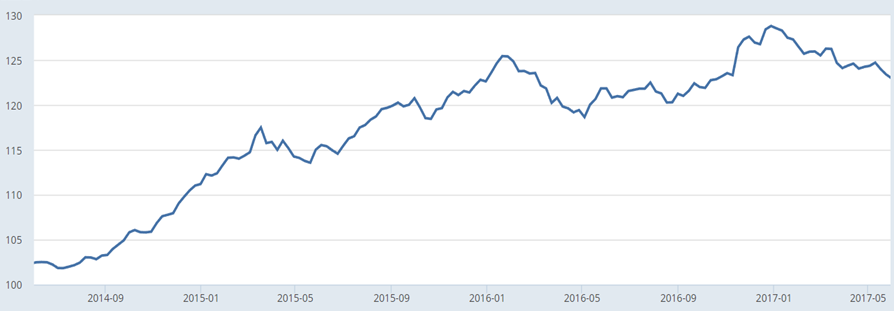

Currency can have a large impact on international equity returns. The past three years though May 2017 are a great case in point. Over that period the U.S. dollar has been on a tear. Exhibit 1 (below) shows the weighted average of the foreign-exchange value of the U.S. dollar against a broad currency basket.

Exhibit 1: U.S. Dollar Outperformance June 1, 2014, to May 31, 2017

Source:Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US)

This U.S. dollar strength has proved a strong headwind for most international equity strategies, as the clear majority of U.S.-based foreign-equity funds do not hedge their foreign-currency exposure. They buy foreign stocks in the currency of each company’s domicile. Thus their returns suffer when those currencies decline against the dollar.

This is best illustrated when comparing the performance of hedged and unhedged versions of the same index. Over the same three-year period, the MSCI All Countries World Index excluding USA returned just 1.26% each year on average. Meanwhile, that same index, when 100% hedged back to U.S. dollars, returned an annualized 6.54%.

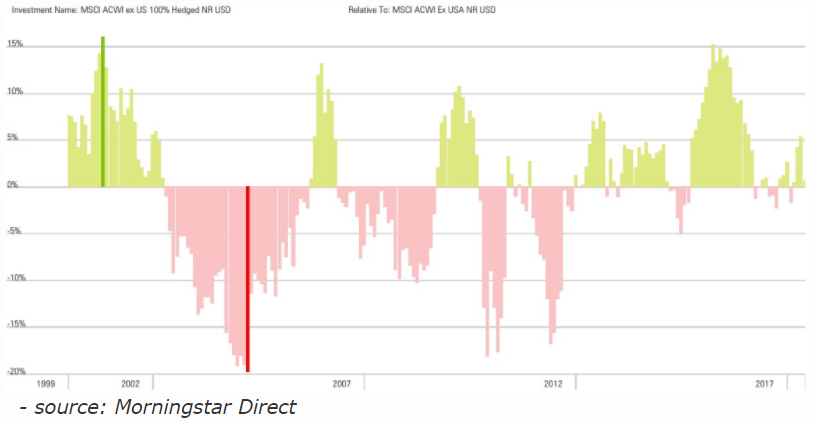

When return differences are that stark, it can be tempting to think that hedging is the way forward. However, there have been many other times over the past 20 years when similar big currency dislocations have occurred. Exhibit 2 looks at the differences in returns over one-year rolling periods between the aforementioned hedged and unhedged benchmarks.

Exhibit 2: One-Year Rolling Performance of Hedged International Stocks Relative to Unhedged

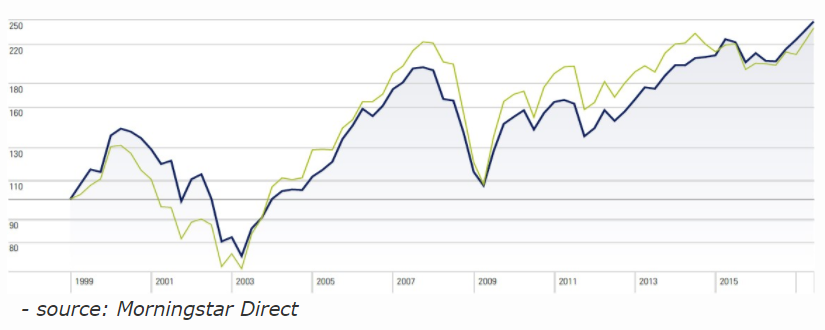

As the chart shows, the dislocation that occurred prior to the financial crisis was even more stark. But back then unhedged equities received the currency boost as the U.S. dollar weakened from 2003 to 2008. Predicting this strength or weakness in advance is extremely difficult to do, especially since the U.S. dollar can remain overvalued or undervalued for long periods. However, these extremes tend to mean-revert over time. Exhibit 3 perfectly illustrates this concept: It looks at the cumulative effects of the above-mentioned peaks and troughs by comparing the same two indexes going all the way back to late 1998, when the hedged index was launched. Despite large differences at certain points in the cycle, the long-run performances of the hedged index versus the unhedged index are almost identical.

Exhibit 3: Cumulative Hedged Versus Unhedged Performance

Despite this, there may be good reasons why an investor would want to reduce the short-term currency effects on their portfolio. If that is the case, there are options available. There are managers would fully hedge its non-U.S. currency exposure back to the dollar; managers might also prefer to let stock selection rather than currency fluctuations drive performance. On the other hand, managers will hedge selectively when they think a currency's value has moved far out of its normal range.

While the divergences in Exhibit 2 show that there is money to be made from strategically hedging, the pool of investors who have managed to consistently add value here is tiny. Therefore, if time is on your side, the diversification benefits of being unhedged (and adding foreign currencies to your asset mix) through a market cycle likely outweigh the shorter-term rise in volatility. Remaining unhedged is also cheaper and often more tax-efficient.