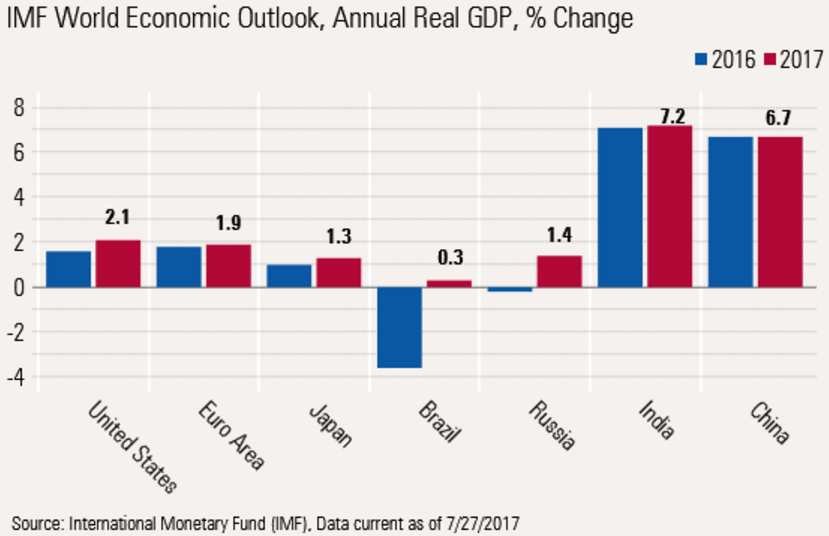

IMF agreed with our assessment in its latest Global Economy Outlook (July), reducing the U.S. GDP growth forecast from 2.3% to 2.1%, while raising Europe's growth rate for 2017 from 1.7% to 1.9%. Even China's growth forecast was raised modestly from 6.6% to 6.7%. Overall, the world GDP growth rate was left unchanged at 3.5%, which is higher than the 3.2% reading recorded in 2016.

The relatively anemic U.S. growth is not because anything is falling apart, but because demographic and labor shortages continue to press on growth rates. Perhaps this is most apparent in the housing sector. Plagued with labor shortages (along with lack of well-located land), it could be doing noticeably better with more skilled construction workers.

In its quarterly economic forecast the IMF left its GDP growth forecasts for 2017 and 2018 at 3.5% and 3.6%, respectively, compared with 3.2% in 2016. The better forecast is the result of a combination of better reported economic performance in the first half, improved trade data, and higher commodity prices (which will boost some emerging-markets economies, such as Russia and Brazil).

After a nice bounce following a worse-than-typical recession, world growth has struggled to get back to long-term averages. Demographics (slower population growth as well as an aging population) seem to be limiting growth not only in the U.S., but also around the world.

On a 10-year averaged basis, growth was generally on a downward track since the baby boomers reached maturity in the 1960s and 1970s. World growth stepped out of its rut in the late 1990s and early 2000s as China's growth accelerated with new government policies.

Not only did China grow rapidly but it represented an increasingly large portion of GDP. China's large demand for raw materials also stimulated the economies of a lot of other emerging-markets countries. However, as China's growth slowed and became less commodity focused, world economic activity entered another languid growth phase in 2011.

Since its last update in April, the IMF has increased its growth rate expectations for Europe, Japan, and China, while it reduced its forecast for the United States. This mainly reflects reported first-half growth that was stronger than the IMF had been forecasting, except in the United States.

It noted the completion of elections in most of the developed world and put to rest some of the uncertainty that had so spooked the IMF earlier. However, it mentioned that some of the election uncertainty has been replaced by worries about if (or when) new stimulus and other policy changes would be implemented in the United States.

The shifts in regional expectations are even more dramatic when compared with the IMF of July 2016. In fairness, that forecast was produced just after the Brexit vote. The IMF slammed its growth rates for Europe itself and a lot of its trading partners, while boosting its growth rates for the U.S., which appeared well on the way to electing Hillary Clinton.

As world growth picked up (except in the U.S.) and OPEC demonstrated some production discipline, commodities began to act at least a little better, which has improved growth in commodity-related economies, primarily emerging-markets economies.

Exhibit 1:

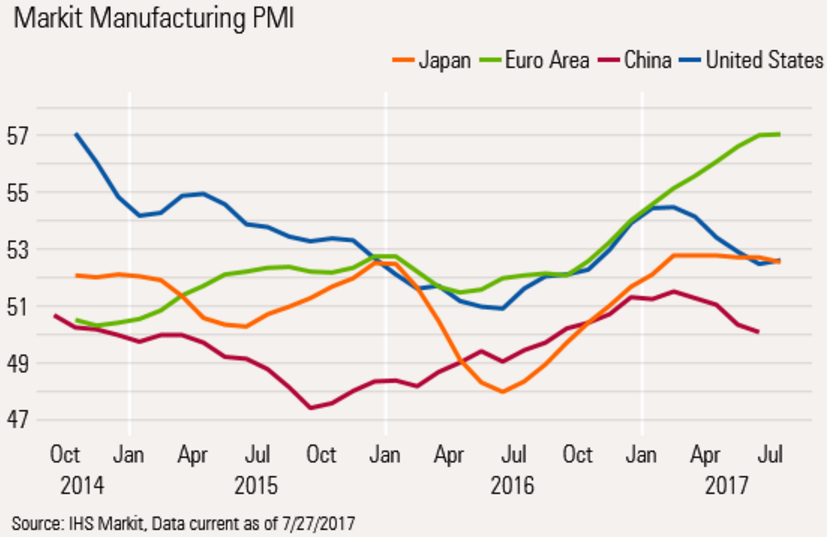

It is not just the IMF data that is showing a generally improving world economy and shifting regional growth trends. Flash purchasing manager data from Markit demonstrated very similar trends. PMI data bottomed around the world in July 2016. Since then, Europe has shown the most improvement and the U.S is not growing as fast as it was at the beginning of the year. Chinese data still looks a bit soft.

Exhibit 2:

To sum up, a lot of people had hoped earlier in the year that those things would be a big help. They're a help, but it's not any more than people expected and maybe even just a slight bit less. Certainly, it's not going to be the savior of the economy, the manufacturing or housing. We're going to need something else to really kick it in to accelerate growth here in the second half.

The information contained within is for educational and informational purposes ONLY. It is not intended nor should it be considered an invitation or inducement to buy or sell a security or securities noted within nor should it be viewed as a communication intended to persuade or incite you to buy or sell security or securities noted within. Any commentary provided is the opinion of the author and should not be considered a personalised recommendation.