Imagine you've entered a poker tournament and have the choice to sit at one of two tables. Seated at table one are enthusiastic newbies you surmise as being likely to show their hands, bluff badly, or make otherwise unwise bets. At the second table are players you recognize as contestants from the World Series of Poker. You might relish the challenge of taking on the latter, but playing the amateurs instead of the pros would maximize your chances of winning. The table of amateurs offers what the insightful strategist, author, and professor Michael Mauboussin calls "the easy game." Easy games are those whose players aren't very skilled, and the payoff from winning is high.

Games like these have become scarce in investing, Mauboussin argues, because less-informed investors have moved to passive investments, leaving the most skilled investors to compete against each other. Technology, both because it promotes transparency and can be used to efficiently sniff out market anomalies, has also helped make investing a harder game to win.

If there are still easy--or at least easier--games in the public markets, we might expect to find them in the small-cap arena. It's not that small-cap investors are any less skilled than their large-cap counterparts. Their playing field is bigger and less crowded than in large caps. Small caps account for a tiny slice of the stock market's total value, but there are 3 times as many small-cap stocks as large caps, according to data from O'Shaughnessy Asset Management. The largest stocks are more liquid and therefore attract more assets from institutions. Such neglect should leave more under-exploited opportunities in small caps than in the large caps.

On the other hand, similar forces have been at play in small caps as in large caps. Over the past five years, passive funds' share of small-cap assets rose from 29% to 46%. (Passive large-cap funds' share grew from 35% to 48% over the period.) The tide of passively managed dollars should push out less-capable small-cap managers just as they would large-cap managers. The game for small-cap managers could be just as tough.

Small Caps: The Easier Game?

A contest against less-skilled minor-leaguers is the easy game. Similarly, if small caps offer more opportunity than large caps, we might expect the best-performing small-cap funds to outperform by greater margins than the best-performing large-cap funds. Put another way, small-cap funds should have an easier time running up the score.

To test this proposition, I divided the active U.S. equity fund universe into large-, mid-, and small-cap buckets using return data from August 1997 through July 2017 on a gross-of-fees basis. The data set includes a single share class from every fund in existence over the 20-year period--nearly 4,800 in all. (Including all funds, not just the ones that are still around today, limits the impact of survivorship bias in the data.

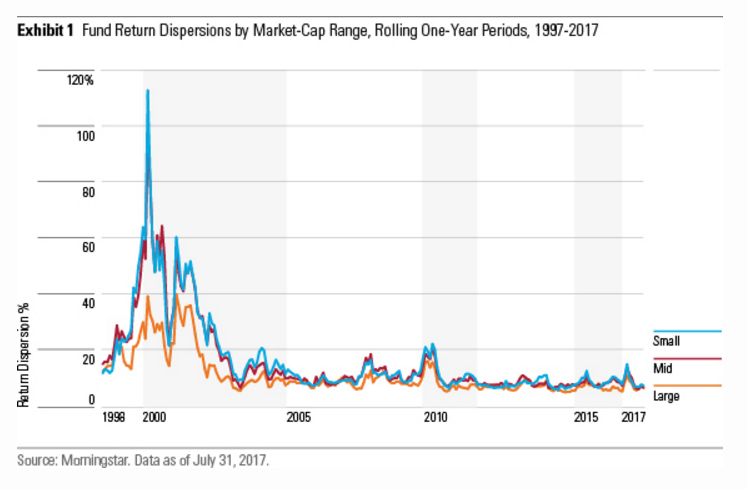

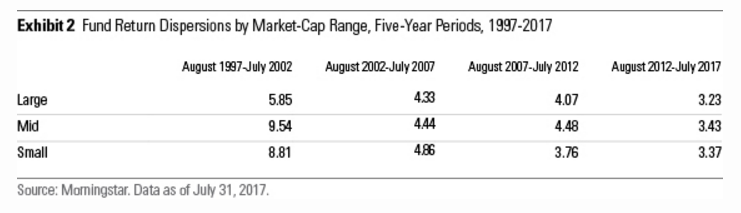

I viewed the difference, or dispersion, of returns between the best and worst performers across market-cap buckets through two lenses. I first sliced the data into rolling-one year periods to examine the historical trend. Because one-year periods can be noisy, I broke the two-decade stretch into five-year increments to get a longer-term perspective. I calculated the dispersion of returns between the 20th and 80th return percentiles to mute the impact of extremes.

The technology-fueled insanity of the late 1990s and its hangover in the early 2000s created massive disparities, especially in mid- and small caps, between the best- and worst-performing funds, as Exhibit 1 vividly illustrates. That this gap would shrink was inevitable. Such extremes, at least of the late-1990s variety, are historical anomalies. Had I started the clock in 2002 instead, the story would be less dramatic, but it would tell a similar tale. The trend continued to slope downward--a sign the game for active managers continued to get progressively harder.

The game doesn't look any less difficult for small-cap managers. Dispersions shrank to similar levels across market-cap ranges over the past two decades. In the most recent five-year period ended July 2017 (Exhibit 2), there were only slightly larger return dispersions in small-cap funds than in large-cap funds. In the prior five years, though, the gap between the strongest and weakest small-cap funds was smaller than for mid- and large-cap funds, suggesting there could be times where smaller names offer the narrowest opportunity set.

The mid-cap group witnessed the widest performance disparities over all five-year increments studied. This finding is more ambiguous. The mid-cap categories are a motley crew, including pure mid-cap funds, all-cap funds with sizable large- and small-cap stakes, and small-cap-focused managers who hang on to winners that have appreciated into mid-cap territory. Greater dispersion among mid-cap funds may not signal so much that mid-caps are an especially fertile hunting ground but that the mid-cap categories are more heterogeneous.

While dispersions narrowed overall, they spiked in more-volatile environments--suggesting there are times where small caps offer outsize opportunities. In addition to the late 1990s and early 2000s, the dispersions between large caps and the rest widened out significantly during the bull market of the mid-2000s as well as the 2008 financial crisis and the 2009 rebound. This isn't the same thing as saying small-cap funds necessarily benefit from high-dispersion environments, however. In 1999, for example, small-growth funds rode high along with soaring tech stocks, while small-value funds sunk along with old-economy industrials names. As the bull market ended in March 2000, this scenario reversed. Opportunities for adding value were high in both periods, but the winners were entirely different.

Of course, the fact fund returns are more narrowly dispersed isn't proof positive the opportunity set has shrunk. The problem might not be so much lack of opportunity in small-caps but a lack of small-cap managers taking advantage of opportunity. Managers often let their asset bases get too big and are hamstrung by benchmark-hugging investment mandates. Opportunity may still knock, but some managers may not be able to answer.

What Does Fund Performance Say?

If the opportunity to add value is greater in smaller names than larger ones, then active small-cap managers should enjoy more success against the passive alternatives than active large-cap managers. Morningstar's Active/Passive Barometer, which measures asset-weighted active fund returns against passive investments in the same Morningstar Category, suggests this has been the case. Over long periods, small-cap funds have been more likely to outperform their index fund rivals than mid- or large-cap funds. Unfortunately, only a minority of small-cap funds did so. Just 26% of small-blend funds alive in June 2007 went on to outperform its passive competitors over the subsequent 10-year period. The average small-blend fund returned 6.3% annually on an asset-weighted basis, versus 7.5% for small-blend passive vehicles.

Of course, even fewer large-blend funds succeeded in outpacing index peers and lagged by even bigger margins. Just 14% of funds in the category survived and outperformed over the 10-year period. And the typical fund in the category trailed the passive alternative by 1.5 percentage points annually.

Conclusion

That the small-cap game has gotten tougher is the reality investors must face. There is, of course, the option not to play it at all. And that's a fine option. There are still ways, though, to play the game smarter. To better your chances, the surest and easiest tactic is to minimize costs. Focusing on the cheapest quartile of small-blend funds improved the odds of outperformance from 26% to 46% over the past decade. The nice thing about the cost advantage is that it's in your direct control. And you benefit from it no matter how efficient the small-cap market becomes. Match low costs with a sound process and disciplined manager, and you've stacked the odds further in your favor.

While there have been windows of opportunity for small-cap managers, there are long stretches where they have been scarce. To be successful, investors will have to endure periods--possibly long ones--where active managers have a tough time distinguishing themselves. Moreover, periods of more-abundant opportunity may not feel like it at the time. That's because they coincide with more-volatile environments, where investors have a hard time sitting tight. What is true for investing in other asset classes is true in small caps: Patience is usually a virtue, especially for investors looking to win the hard game.