Academics promoting passive investing have argued that active managers do a poor job of beating their respective benchmarks. Fees are the most cited reason for this underperformance, with a higher fee structure prompting investors to reconsider the value they are getting.

This is combining with regulatory pressure and increased transparency, highlighting the ever-present importance of considering fee structures in the investment selection process. Yet, to comprehend the fee drag at a portfolio level, one must consider both the absolute level of returns that can be expected as well as the potential for gain. To illustrate, we must consider whether an investment can generate value, and this is commonly achieved by dealing with the dispersion of returns.

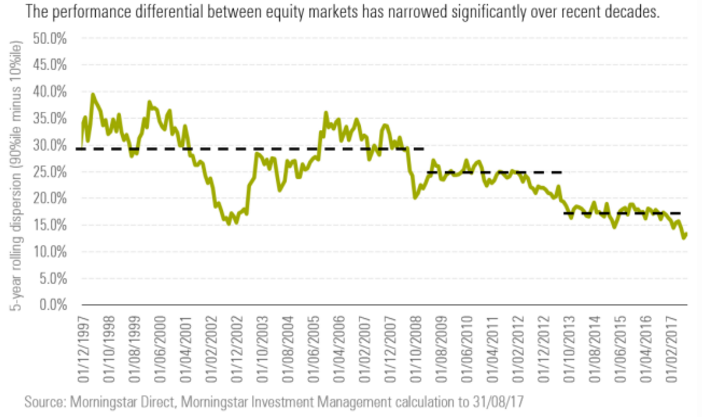

Dispersion can mean different things to different people and is especially sensitive to the way one defines it. Yet, most commonly, people think of dispersion as the range of outcomes that can be expected. For instance, in the chart below we show the history of the broad global equity universe – illustrating the gap between the strongest performers versus the weakest, by assessing 47 key country markets and the gap between the 10th and 90th percentiles over five-year rolling periods.

The central idea is to identify the range of outcomes an active investor would have to choose from. We can see that the dispersion level has gradually dropped and is now at a level not seen in the past 20 years – where the range of outcomes is only 13% versus as high as 40% in 1998. While one must be careful when considering its permanency, it is a staggering statistic that could potentially illustrate the challenges being faced by active managers in recent years.

To quantify the relationship dispersion has with active management success, we can assess the dispersion of markets against the excess return achieved by the average active manager in the Global Flex fund category relative to its index benchmark – where we find an incredibly strong relationship, especially over the past 12 years. In fact, statistically speaking, an extreme case leads this metric to an r-squared of 0.85 since 2005, meaning approximately 85% of the variability in a manager’s recent success, or lack thereof, is said to be explained by the dispersion of the market.

The obvious question to ponder is whether this is coincidental or causal – and if so, whether it is a cyclical or structural phenomenon. For example, a structural case would suggest that access to information is easier than ever, meaning an “informational edge” is increasingly difficult to maintain. Globalisation could also play its part, as investors gain access to a more diverse set of markets that were previously off limits; for example, demand shifted as China opened their doors to foreign investors.

However, a longer-term view of dispersion – as shown above from 1973 – shows that a cyclical element is likely at play too. To explain, one may not need to look any further than the six global recessions since 1970: 1974–75, 1980–83, 1990–93, 1998, 2001–02, and 2008–09. While imperfect, each of these recessions saw dispersion increase either during or in the aftermath of the economic stress.

Therefore, while our intuition leads us to see a causal connection, a wider range of outcomes should allow for greater value generation, the low dispersion at present may simply reflect the enormous quantitative easing programme that has shifted markets materially over the past 10 years. We have experienced one of the longest economic expansions in recent memory and strong asset flows into growth assets have “lifted all boats”. Therefore, should we see a market correction or recession – or simply a sustained period of wider dispersion – this could trigger a resurgence in active manager success.

How Should an Investor Use this Information?

Dispersion is clearly an important factor when assessing the fate of the active management industry. The first step is to acknowledge the challenges active managers face when dispersion is low, and to then realistically contemplate what value each manager offers in a portfolio context.

While there are limitations to the analysis; for example, it is possible that country and sector dispersion is low, but stock dispersion is wide – especially as we have ignored size/weight, it does tell us is that investors should garner a better understanding of the managers and the ways they deal with lower dispersion.

More broadly, it also raises the importance of fees, where we are seeing an exciting period of awareness and consolidation. The fee drag is a vital component to the investment selection dilemma and lower fees will help end investors obtain better outcomes. This is especially important when dispersion is low, as differences in fee structures can play an important role in an investor’s ability to protect capital from the erosion caused.