Exchange-traded products belonging to Morningstar’s “dividend” strategic-beta group form one of the largest contingents within this universe as measured by assets under management. As of the end of May 2019, these funds collectively held US$173 billion of investors’ assets in the U.S.

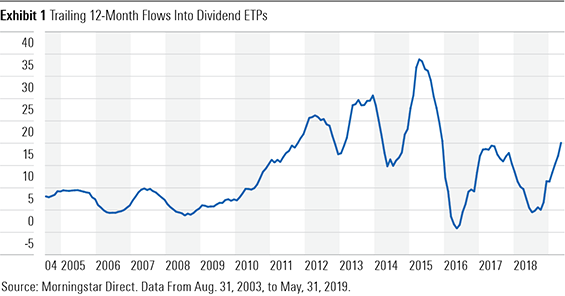

This group has been growing at a blistering pace in recent years. During the trailing decade, dividend ETPs in the U.S. have attracted nearly US$133 billion in new assets.

This should come as little surprise in the context of the prevailing interest-rate regime and the secular upward trend in demand for sources of investment income, as the first waves of baby boomers have entered retirement.

Asset managers have taken notice, and product proliferation is in full swing. Of the 140 dividend ETPs that exist today, just under half are less than five years old. As the menu of dividend ETPs expands, it is important that investors understand that not all dividend ETPs are created equal. Each has its own unique characteristics, which stem from important--albeit often nuanced--differences in the methodologies of their underlying benchmarks. Understanding three key characteristics of these funds can help investors make more-informed choices. These include dividend yield, dividend growth, and dividend durability.

Dividend Yield

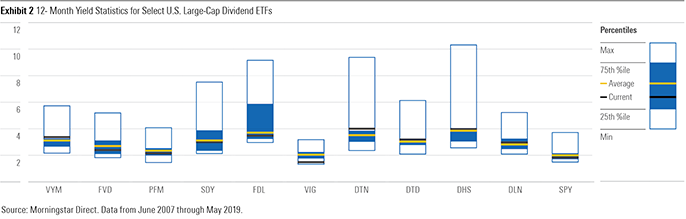

A fund’s current dividend yield is often the first metric investors seek out when shopping for equity-income opportunities. The 12-month-yield metric aggregates an ETP’s distributions during the trailing 12 months and then divides that figure by the fund’s net asset value. While this metric is interesting, it is not very useful in isolation, because it lacks context.

Framing a fund’s 12-month yield in the context of its historical values and relative to the current and historical values for comparable strategies provides useful context. For example, Exhibit 2 plots the current, average, maximum, minimum, and 75th and 25th percentiles of the monthly 12-month yields for dividend exchange-traded funds that invest in U.S. large caps and that launched before 2007. It also includes SPDR® S&P 500 ETF (SPY) as a point of reference.

It is apparent, based on a passing glance at this exhibit, that these funds’ yields can be quite volatile over time. It’s also obvious that they can diverge dramatically from one another. At the end of February 2008, the highest-yielding fund of the lot, WisdomTree US High Dividend ETF (DHS), had a 12-month yield of 10.32%, while the lowest-yielding fund was Vanguard Dividend Appreciation ETF (VIG), with a 12-month yield of 3.09%. That’s a spread of 7.23 percentage points. The market downdraft provided a useful testimonial to the importance of understanding the particulars of the construction of these similarly labeled funds’ underlying benchmarks. The former loaded up on stocks whose payments proved unsustainable, including many financial services firms; the latter looks to roll up stocks that have raised their dividends in 10 consecutive years, which is a sign of durability. Those ETFs that focus on higher-yielding stocks tend to take on more risk than others when they go about building an income-oriented portfolio. A high dividend yield may indicate that the market has soured on a firm’s prospects and may be skeptical of its ability to continue to maintain its dividend at its current level. Cuing on dividend yield will lend a value orientation to a portfolio, but it may put you at risk of catching a falling knife (or two).

In part two of this article, we will discuss the other two key characteristics -- dividend growth and dividend durability.